For those outside the industry, the term “complaint handling” conjures visions of angry customers arguing with tone-deaf service representatives. If you’ve ever had a dispute with your mobile phone carrier or insurance company, you probably know what I mean. Yet, complaint handling in the device industry involves so much more than placating upset customers. It’s a regulatory requirement and a risk-reduction imperative.

In this guide:

First and foremost, complaint handling is a business and regulatory requirement. If you are going to be in the medical device business, you must document a process for gathering feedback. If you are new to complaint handling, you will first want to start by reading the requirements for complaint handling as spelled out in US FDA regulation 21 CFR Part 820.198 and Clause 8.2.2 of ISO 13485:2016. (The ISO 13485 standard is a copyrighted document so you won’t find the text online, but you can buy it from ISO.)

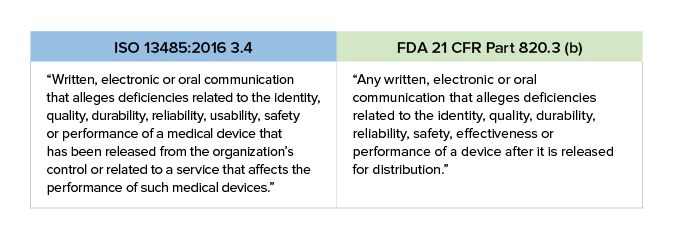

The word “gather” is important because it implies we are proactively seeking feedback. Complaints, unfortunately, come to us, so complaint handling is a reactive procedure. Let’s take a quick look at the definition of complaint handling according to ISO 13485:2016 and 21 CFR Part 820.

One thing you should note is the inclusion of the word “usability” in ISO 13485:2016. This is an increasingly important issue to which you need to pay attention. The US FDA refers to usability as “Human Factors.”

Feedback and complaints come from a variety of sources, including surveys, focus groups, data analysis, service requests, technical support inquiries, and even online product reviews and social media. All complaints are feedback, but NOT all feedback is a complaint. The following types of feedback are not complaints:

This is important to understand, because you need to establish a process to evaluate each piece of feedback and determine whether it meets your requirements to elevate it to a complaint. We’ll talk more about this later.

Complaints can originate from many sources and be submitted via email, online contact forms, telephone (by far most common), social media, online product reviews, and even good old-fashioned letters. Often the complaints will be submitted directly from customers, but they may also come second-hand from customer service personnel, your sales team, or field service personnel. It is vitally important that every employee be trained on how to deal with the intake of complaints, as this is required in the US by 21 CFR Part 803.

Essentially, postmarket issues can be placed into one of two buckets. The first type is an “incident-driven” issue. For instance, let’s say you receive a report from a hospital that an electrical malfunction has occurred in your surgical ablation system tool. The failure could have led to serious harm or death for the patient. This is an incident-driven issue that requires immediate action.

The second type of issue that arises is one driven by a review of data. For example, while reviewing service records you may notice a trend in repeated failures of your surgical ablation pens under certain conditions, which qualifies as a complaint. That’s certainly a reliability problem and falls within the ISO 13485:2016 and FDA definitions of complaints.

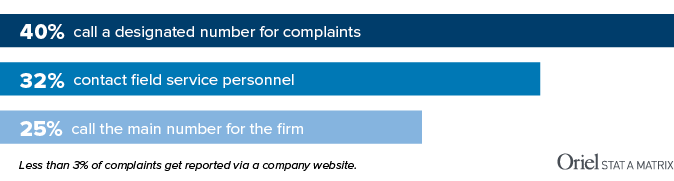

You may assume that the majority of complaints get reported via the “contact us” form on a company website or a specific email address posted online. Believe it or not, only 3% of medical device complaints come via these channels. In the medical device world, the telephone still reigns supreme. Nearly two-thirds of complaints are reported by telephone. Surprised? The reality is that when people experience a problem with a device, they want to talk to a real person about it right now, not submit an anonymous online form/email into a black hole.

In our increasingly impersonal online world, the process of fielding phone calls from angry customers may seem time-consuming and unpleasant, but it’s worth it. You WANT people to call you because it gives your team an opportunity to ask questions and dig into the underlying issue. A good service rep – trained to listen, probe, and show empathy – can dilute the venom of an upset customer while gathering the data needed to further investigate the claim.

Before we talk about reporting, we should take a look at the basic complaint-handling process, which has three phases.

STEP 1 Intake – This is where you do initial triage. Is the complaint valid? Is it potentially reportable? Was it caused by use error or abnormal use?

STEP 2 Investigate -This is where you dig in. How deep you go will depend on the nature of the complaint. In many cases, you will conduct an initial investigation and determine that no further research is necessary. On the other end of the spectrum are incidents where harm was done to a patient or user. These need to be thoroughly investigated to determine the root cause of the issue.

STEP 3 Close – After you determine the level to which you need to investigate and have assembled the appropriate documentation as required, you will “close” the complaint. While you are investigating and closing complaints, you may also be updating your risk management files, preparing a vigilance report, and/or – in extreme circumstances – taking immediate action to mitigate further harm.

Before we get into the issue of whether a complaint is reportable, let’s talk about what information needs to be captured when a new complaint is received. There is specific information that, at a minimum, you must collect. This includes:

During the investigation phase, there will come a moment when you need to decide if the complaint is reportable to regulatory authorities. FDA refers to this as “medical device reporting.” Europe uses the term “medical device vigilance,” while Canada calls it “mandatory problem reporting.” Regardless of the market, reporting is required when you become aware of information from any source that suggests your product may have:

If you decide not to report something, it is absolutely vital that you document the reasons why you made this decision. When in doubt, report it.

During the intake process, a determination will need to be made of whether a complaint is considered a reportable event. Here is a list of incidents that are reportable in many countries:

Here are some examples of reportable incidents. Keep in mind that the requirements differ among the US, Europe, Canada, and Australia, so make sure you understand the reporting requirements for each market in which you sell you product. Reporting requirements often apply even if the incident did not occur in that market!

Remember, if you choose not to report an incident, you need to document why you chose made this decision. Otherwise, you could later be accused of brushing known problems under the rug. When in doubt, pass it along for further investigation or report it.

Europe’s Medical Device Regulation (MDR 2017/745) places strict requirements on medical device manufacturers to report incidents to EU Competent Authorities. Serious incidents need to be reported within 15 days of becoming aware of the issue. All of that information will also be stored in a database that allows Competent Authorities in different EU countries to share information; however, at this writing, the database has not yet been released for use.

Typically (e.g., when public health is not threatened) FDA requires medical device reporting within 30 days of becoming aware of an issue, and that’s consistent with the current EU Directives. There are exceptions that may require you to report a serious incident in as few as 5-10 days, so make sure you understand the requirements.

With the EU Regulation now requiring a 15-day reporting timeframe after you become aware of an issue, this means your complaint-handling unit has to be really efficient!

You may be able to close the complaint after an initial investigation into assignable cause. Is there an open CAPA for this issue? Does the complaint suggest that a closed CAPA action was ineffective? Is this being investigated by another entity, such as a supplier or distributor? Make sure you understand when to escalate to Level II and when an initial investigation is enough. In all cases, document, document, document.

After your initial Level I investigation, you may find it necessary to investigate the probable cause to find out if there is a new problem. That’s usually due to the fact that a new (previously unreported) issue has occurred, or your trend alerts have been exceeded. At this point you may choose to end an investigation because the failure is within the limits you have established based on labeling, intended use, and risk files. Or, you may have a situation in which the failure is a known issue but falls outside a risk threshold or trending (frequency) limits. These risk thresholds or trending limits are outputs of your risk management process. For example, in design you reduced the risk of battery failure by adding a backup battery, but you still want to trend failures of the first battery. The failure rate is pretty low, as expected, but then you see a sudden shift upward in the occurrence rate. This triggers you to investigate, uncovering a supplier issue and allowing you to solve the problem before any patients are harmed.

If your Level II investigation reveals that you have a new failure mode on your hands, you may need to take the next step and open a CAPA. You certainly need to update your risk management file. Before doing so, you need to define the problem and then investigate its root cause. You will also need to determine whether a recall is needed or if some other corrective/containment action is warranted. It’s important to know that not all complaints require a root cause investigation or CAPA! That being said, there are some events that may require a root cause investigation:

So, now that you have conducted your investigation and taken appropriate actions, it’s time to close the complaint. Before you begin that process, you need to document parallel processes such as vigilance reporting, risk management file updates, and CAPA, if applicable. If you ended your investigation after Level I, you need to document in your complaint files that further investigation was not required and why. It’s important that you codify the closeout type so you can use this for trending.

If the complaint proceeded to Level II but ended there, you will again need to document why a root cause analysis was determined to be unnecessary. Include all data and reports, as well as a summary statement for the complaint file.

Finally, if the complaint proceeds all the way to Level III and you end up preparing a CAPA, your system may allow you to close the complaint by referencing the ongoing work in the CAPA. This is useful, as you may have additional complaints for the issue before your corrections and corrective actions are implemented.

Finally, you need to have a process established so that you properly communicate the issues to the appropriate people internally (and perhaps externally). After all, investigating the root cause of an issue is time wasted if that knowledge is not shared with the people who can prevent the issue from happening again.

Internally, your design team incorporates complaint information as an input to design changes. Your manufacturing team incorporates complaint information as an input to improve their processes. Internal communication mechanisms include:

Customers may need feedback for their own records, and customers also include regulators. External communication mechanisms include:

A well-developed and well-executed complaint-handling and reporting process has a lot of moving parts and can sometimes feeling burdensome to the company. You need to develop clear metrics to track safety and quality and then train your employees on these metrics. Without clear metrics, you won’t be able to see whether you are making meaningful progress or spotting trends. Numbers aside, always remember why you do it: to continually improve the safety and effectiveness of your devices for patients and users.

According to the FDA, postmarket surveillance is the process of “active, systematic, scientifically valid collection, analysis and interpretation of data and other information about a marketed device.” Europe has a similar definition but adds the word “proactive” – a systematic procedure to proactively collect and review experience gained from devices placed on the market.

If you are just getting started building an internal PMS process, the first thing to do is organize a team that will manage product safety and quality. This may include representatives from QA/RA, manufacturing, design, field sales, and technical support. You will also want to be sure you have medical or clinical expertise and the support of your legal department, as they will be more involved than you may think. The structure of PMS teams will vary depending on the size of your company, its organizational structure, and geographic dispersion of locations.

Once a team has been identified, you’ll want to structure activities to continually assess the balance between the risk of the device and the clinical benefit, taking into account the state of the art in technical innovation. (See our highly rated risk management class for more helpful information on determining clinical benefit.) From a practical sense, this means both a reactive (incident-driven) process as well as a proactive (review-driven) process.

Reactive (incident-driven) PMS: Part of this process will involve the maintenance of risk management files and a clear definition of the trigger events that necessitate further investigation of complaints. Other examples of reactive PMS are:

Proactive (review-driven) PMS: This can include many nontraditional sources, such as social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram and X), online product reviews, online discussion forums, or blogs. As part of PMS activities, have a plan or method for evaluating this information. Other examples of proactive PMS are:

Once you have organized your team and established a framework for gathering PMS data, you need to translate data into information. This is where complaints, PMS, and risk management intersect. Evaluate the information using sound statistical rationale and objective risk-based decision making. Continually assess the intended use and actual use of your device, and the clinical benefit the device provides to maintaining public health. Many organizations evaluate information but fail to take credit for this in updating their risk management files. You don’t want an audit finding for failing to document the good work you are doing in evaluating PMS information.

Finally, you need to have a process established so that you properly communicate the issues to the appropriate people within the company. Complaints and PMS are important inputs to management review, and outcomes of this review include resources and actions. After all, investigating the root cause of a failure is time wasted if that knowledge is not shared with the people who can prevent it from happening again.

Any company that has endured a high-profile product failure issue can tell you that the cost of maintaining an effective, proactive complaint-handling process is far lower than the cost of a preventable recall, patient harm, or PR disaster. Yet, although it is required in ISO 13485:2016 and 21 CFR Part 820, many companies do not have a complaint-handling process and discover this the hard way during an audit or a field failure. We know this because FDA keeps excellent records and “lack of complaint-handling procedures” is one of the most oft-cited violations.

This is a bigger deal than ever before, and it’s being driven by changes in European regulations. Compliance to the new EU MDR requires more emphasis on postmarket surveillance (PMS) activities, especially postmarket clinical follow up (PMCF). Chapter VII of the MDR (2017/745) points out the specific requirements for PMS and the data that must be collected. This includes information from Field Safety Corrective Actions (FSCA), Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSUR), plus data on trending, minor incidents, and general feedback. Annex III of the MDR also states that you must have a proactive and systematic process for collecting and analyzing postmarket data.

Check out our intensive training classes on Medical Device Complaint Handling, Event Reporting, and Recall Management and Medical Device Postmarket Surveillance (PMS) Implementation. Both classes are offered as public seminars, either in person or virtually, or can be held just for your company.